A number of articles in this Knowledge Base fall in the category of Best Practices.

The info in each article is not just my opinion. Instead, I’m sharing hard-won knowledge gained through being in the audiobook industry for 20 years, listening to hundreds of audiobooks, attending continuous training and conferences, judging in the Voice Arts Awards for multiple years, voraciously reading articles, and daily discussing the topics with peers and producers in person and on-line. I also am republishing some excellent advice generously shared by other well-respected industry pros.

You can and should do your own listening and research to be aware of best practices and changing trends in the industry.

Start by listening to audiobooks published by the big 5 print publishers. If you don’t know who they are, a Google search will help you learn the answer. Learn to start with Google for most things you want to know. In this case, I’ve also included the Big 5 in the Glossary.

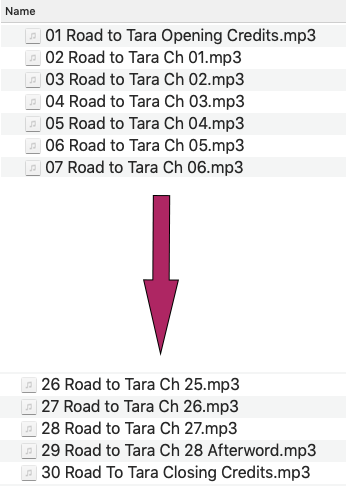

Subscribe to AudioFile Magazine and listen to the audiobooks in genres that interest you and especially those that earned Earphone Awards. Listen to audiobooks that earned Audie Awards from the Audio Publishers Association, Grammy awards from The Recording Academy, or any of the other dozen types of awards listed on this Audible page. Choose books with narrators who have been inducted into the Audible Narrator Hall of Fame and/or AudioFile Magazine’s Golden Voices.

If your rights holder asks you to do something that you haven’t heard done before, chances are very good that it isn’t done for a reason.

In addition, a narrator should seek out coaching to improve text analysis, performance skills, and workflow. This article and those linked within it will help you evaluate a coach.

While you can ask questions in narrator Facebook groups, you need to be very careful about the advice you accept and use. All members of such groups do not share the same level of experience or knowledge about the industry.

Taking a weekend class and/or doing a short book does not make one into an audiobook expert. If someone promotes themselves in multiple roles, such as a narrator, editor, and proofer, they probably haven’t done the requisite work needed to be an expert in any of those disciplines.

I’ve also seen some on-line offerings by those who have done a number of short books and are now selling their “secrets” to success rather than becoming a better narrator. For instance, one product states “Don’t be too concerned about a lack of experience when you are just starting out.”

Wrong.

If you are presenting yourself as a professional narrator, you are implying that you have the knowledge and skills to complete the job. You can volunteer to gain experience.

Do some research before accepting advice from someone unknown to you:

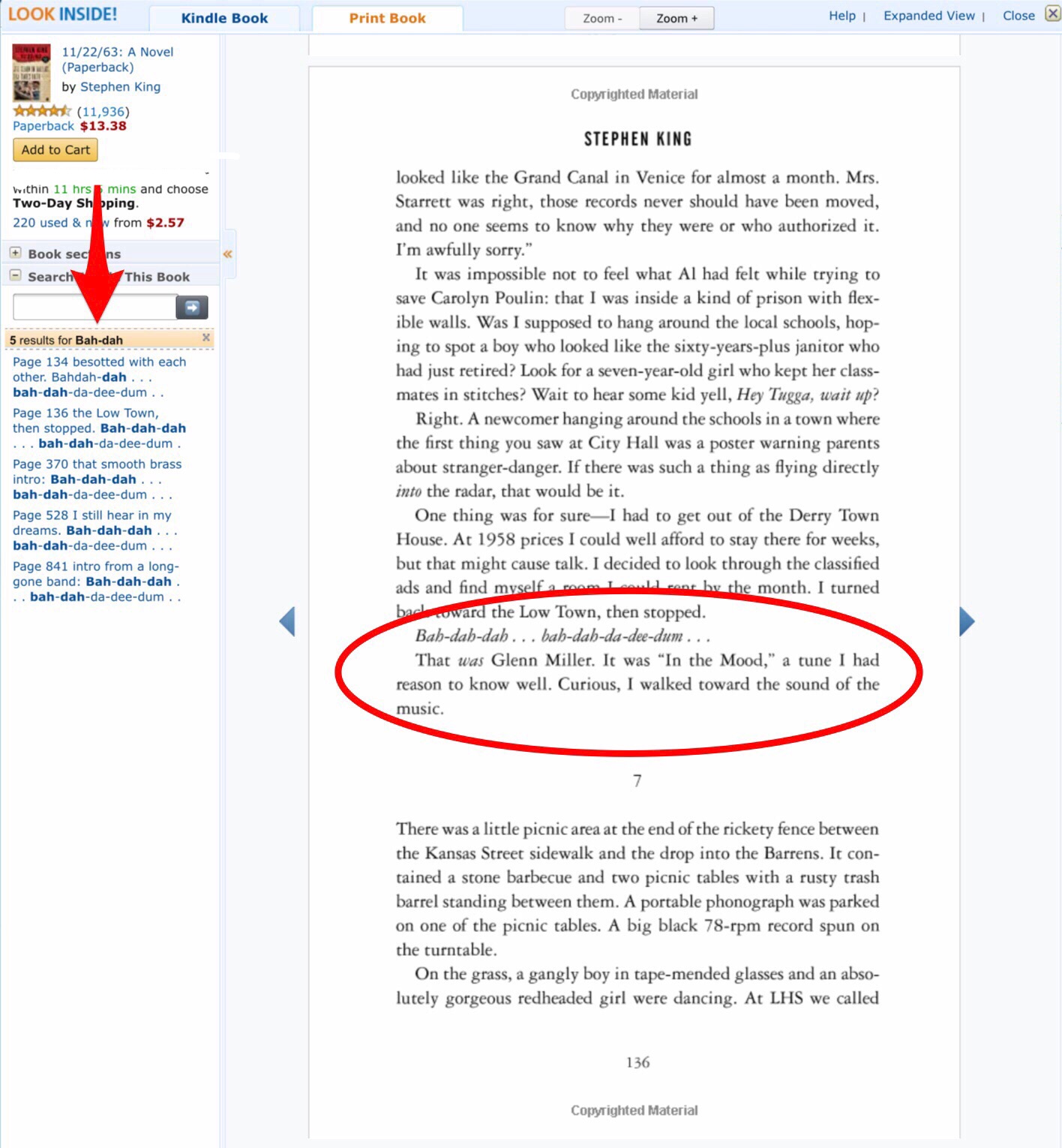

- If the person is another narrator, look up their portfolio on Audible.com. Listen to some of their samples and look at the customer ratings and comments. How many books have they done with durations longer than 6 hours?

- Check the person’s web site. How do they present themselves? Do they have professional reviews or awards?

Other resources on this topic:

- Narrator Ann Richardson has written a golden trifecta of excellent articles that all relate to Best Practices:

-

- She discusses 11 general Best Practices in this article.

- Ann offers terrific advice about ethics and etiquette in this one.

- Narrators need to have integrity and set and live up to standards of excellence.